SERVICES

Tuesday October 23, 2012

The Freedom of the City

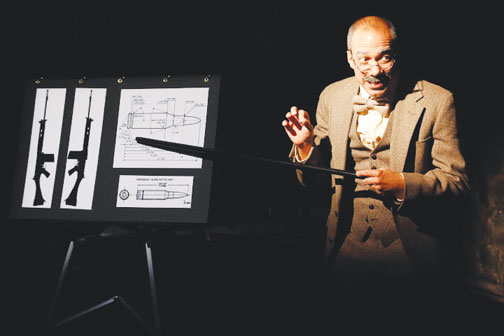

Cara Seymour (as Lily), James Russell (as Michael) and Joseph Sikora (as Skinner) in Brian Friel's 'The Freedom of the City' at Irish Repertory Theatre (Carol Rosegg) By Gwen Orel Just before intermission, a man sitting in front of me at Irish Repertory Theatre's enthralling production of Brian Friel's 1973 play The Freedom of the City turned to his companion and said that the play made him question the information we've been receiving about what really went on in Libya. Friel would love that comment. Although it's 39 years old, and the situation in Northern Ireland has changed for the better since 1970, when the play takes place, The Freedom of the City has immediacy. In its depiction of innocents caught up in a violent situation, for reasons that are partly political but mostly personal, and of the news spin, the political gloss, the heroic martyrdom against the mundane truth, The Freedom of the City is sadly relevant. Nobody interested in the unfoldings of politics and history should miss it. This is an election year, and while nobody is shooting our unemployed - yet - The Freedom of the City reminds us that individual voices are always in danger of being shouted down by those with guns and microphones. The story follows three people who flee poison gas set off in a Civil Rights march in Derry by running into the nearest building with an open door. It turns out that building is the mayor's office, the Guildhall. It's lush and plush and the earnest marcher, Michael Hegerty (James Russell), the downtrodden but funny mother-of-one Lily Doherty (Cara Seymour) and the glib, streetsmart "Skinner" Fitzgerald (Joseph Sikora), have a laugh drinking the booze, trying on the robes, and talking, while the clock ticks, the building is surrounded, and they, and we, know that getting out will not be so easy as getting in. The building, according to the news, a a pretty newscaster (Christa Scott-Reed) informs us, is "occupied." And the play opens with a judge (John C. Vennema) presiding over a fact-finding inquiry about the deaths of three civilians, who supposedly shot first at the troops surrounding the building. You'd think with the outcome never in question there would be no suspense, and that it would all be "Waiting for Gunfire." Yet it isn't, thanks to Friel's skill as a portrayer of human beings and an arranger of a spectrum of scenes that show us the temper of the times, and thanks to director Ciarán O'Reilly's sense of urgency and rhythm. You might feel frustrated by the way the gloss given by the flash-forward scenes of news, inquiry and martyr-praising Irish songs (delivered by sweet-singing Clark Carmichael, dressed as a Clancy brother in an Aran sweatshirt) have so little to do with the truth we see unfolding, and you might feel anxiety and even agony for the three people stuck in their own Dog Day Afternoon, but you won't feel bored. It's a real epic of a play, with scenes in the mayor's office intercut by interludes from an American academic (also played by Scott-Reed) talking about the effects of poverty, the news, the ballads, and the inquiry. The mood of tension is established immediately with gunmen in the house and with a set dressed with graffiti and barbed wire. The look and feel of this play is like a living time capsule. Charlie Corcoran's sets, Sven Nelson's props, David Toser's period costumes, Robert-Charles Valance's hair and wig designs (particularly the academic's crimped 1970's hair), Michael Gottlieb's lighting and Ryan Rymery's original music, with sound design by M. Florian Staab, draw one in so completely to this world that despite the tension it's a sensory treat throughout. Yet it's the three characters, exquisitely portrayed by a top-notch cast, that keep the play alive, even as we know the three are doomed to be riddled with gunshots when they exit. In fact, there is a gruesome scene in the second half involving a doctor (also played by Carmichael) showing diagrams of their many bullet-wounds to the judge. The play, though set in 1970, is a comment on Bloody Sunday in 1972, in which 13 civilians were shot by the British Parachute Regiment during a civil rights march in Derry. An inquiry held shortly afterward found the soldiers innocent of wrongdoing, but, as O'Reilly's program notes point out, Prime Minister Tony Blair set up an inquiry in 1998 and in 2010 Prime Minister David Cameron reversed the findings of the commission. This past July, the police finally began a murder investigation into the civilian deaths.

Evan Zes (as Professor Cupley) in Brian Friel's 'The Freedom of the City' at Irish Repertory Theatre (Carol Rosegg) Knowing this doesn't really make the play much easier to bear as you sit through an ongoing miscarriage of justice and confusion of information (at one point there are reports that there are 40 armed people inside), though it helps a little. There's also a political time line in the program that makes it a keeper. I wish more theatres put real notes in their programs and hope Irish Rep never changes. All of this makes it sound as though the play is an earnest trial, something that might be good for you but heavy. But most of the play is full of laughter and light conversation, because most of it is in the interplay of the three very different characters who find themselves in the mayor's office. Michael is young, serious, engaged to be married and passionately interested in Civil Rights. He's idealistic, having been on every march since they began, and believes that the "hooligans" are causing the problems that led to the police overreacting in a general way. He's unemployed but going to night school, and insists on putting money down for the one drink that Skinner insists he take from the mayor's locked cabinet. He'd be a prig, except Russell plays him with so much boyish intensity that one, like the motherly Lily, just wants to pat him on the head and encourage him. Lily is a corker. She's full of a fun, and when pressed, doesn't really know why she marches - to get out of the house, perhaps? She tries saying it's for one vote, but when Michael tells her they have that, she seems stumped. Her real reasons for marching do come out later, though. She's living in a flat with 11 children, who came out, she says with a laugh, like "a pattern on wallpaper: two boys, a girl, two boys, a girl." Her husband, whom she calls "the chairman," has ruined lungs and cannot work. Seymour shows us her love of life in the way she keeps sipping the sherry, which she hilariously calls port wine, dances with Skinner, gets mad but never offended when Skinner, whom she calls "glib," razzes her, and is easily coaxed into making long distance calls on the mayor's phone. She also insists that Skinner take off his wet clothes and holds Hegerty's head when he's coughing from the gas. Skinner is the authorial stand-in-Friel shows his hand at one point by making the glib man with "no fixed address" quote Shakespeare. Skinner at first seems like a hooligan himself, but he quickly demonstrates that instead he's just one of the poor whom, as the academic Dr. Dobbs (Scott-Reed) tells her class, lives in the moment - and possibly has more fun than the middle class. It's Skinner who quickly unlocks the mayor's liquor cabinet, who finds the red robes of the city to dress up in, who wears a tricorn hat and who, before they go out to die, stabs the portrait of Sir Joshua Hetherington, M.B.E. And when Michael presses him "What do you want?" Skinner, who is part of the 14 percent unemployed, does not answer - the megaphoned voices of the guards surrounding them answer for him. Sikora shows us this wise fool in all of his savage strength. He's charming, glib for sure, a little unpredictable, hungry and decent. It's Skinner who notes that the British took them very seriously, and recalls with regret "how unpardonably casual we were about them." It's also Skinner who signs the mayor's guestbook of important visitors as "freeman of the city" - a play of words on the title "Freedom of the City," which is an honor some towns grant to people or groups for community services. In his death, Skinner has earned that right, and he knows it. O'Reilly's stage tableaux and musical timing keep the play humming into its foregone and powerful conclusion. Gwen Orel runs the blog and podcast New York Irish Arts |

CURRENT ISSUE

RECENT ISSUES

SYNDICATE

[What is this?]

POWERED BY

HOSTED BY

Terms of Service | Privacy Policy

Website Design By C3I