SERVICES

Tuesday March 23, 2010

200 Years Later

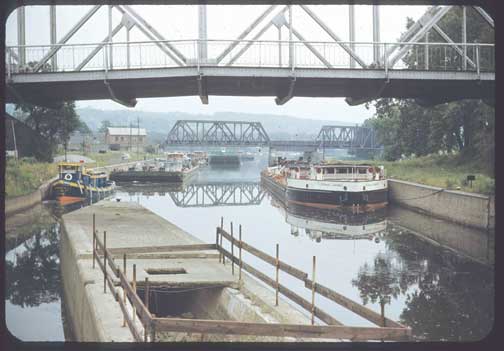

Scene along the modern Erie Canal in Waterford in 1949. The famed tug Urger, left, and M/V Richard J. Barnes (later Day Peckinpaugh), right, are now both listed on the National Historic Register. Pictured in the background are tows waiting to proceed up through the Waterford Flight, which raises boats 170' through five locks in just 1.5 miles (NYS Museum) The Legacy Of The Erie CanalBy John Callaghan The concept of water transportation and its inherent efficiency did not arrive here with European settlers, in fact the Native American population in New York State and throughout the country had a long history of mostly rudimentary improvements to creeks and streams for the purpose of moving goods and people before the first Dutch settlers arrived. But a new nation needed a means to grow and prosper, and it was not long before inhabitants of colonial New York began to muse about more sophisticated improvements to the region's internal waters and the benefits it might bring. The prospect of connecting the eastern seaboard with the "inland sea" - known today as the Great Lakes - with a water level connection was enticing, but few thought it practical or even possible. The first to recognize New York's unique ability to link east and west was colonial New York's Surveyor-General, Cadwallader Colden. Born in Ireland of Scottish descent, Colden appreciated that the only water route through the formidable Appalachian mountain chain from Maine to Georgia was located in New York's Mohawk Valley, where a receding glacier had cut a path between the Catskills and the Adirondacks. Colden opined in 1724 that a canal could be constructed, following the path of the Mohawk Valley, between the Hudson River and the Great Lakes. Though Colden's extraordinary vision represents the origin of the idea of an Erie Canal, it would be just over a century before the Seneca Chief would make her way from Buffalo to New York Harbor, where DeWitt Clinton would merge the waters of Lake Erie and the Atlantic.

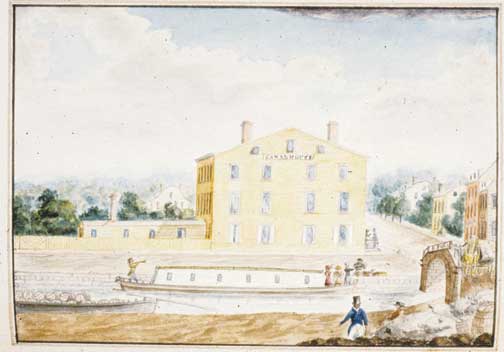

Packet boat on the Erie Canal near Utica (NYS Museum) Before Clinton and others would as much stride across New York in a single step, with a transportation enhancement the likes of which the young Nation had never seen, decades of proposals, political wrangling, and entrepreneurial triumphs and failures would culminate in a series of events which unfolded in the New York State Legislature over a few days in March, 1810. Long before it was derided as being the most dysfunctional legislative body in the country, the New York State Legislature set in motion events which would literally change the face of the Nation, make New York the financial capital of the world, ensure the movement of supplies to Union troops during the Civil War, and make New York the Empire State. Senators Thomas Eddy and Jonas Platt had long ruminated about the future of waterborne transportation in New York. Eddy had also served as a Director of the Western Inland Lock Navigation Company, formed in 1792 by General Philip Schuyler of Revolutionary War fame. The Western Inland had set about making improvements along the route which Colden had identified as having so much promise: the Mohawk Valley. In addition to these improvements, the company constructed a small canal with a flight of locks near Little Falls, NY. Small craft known as Durham boats plied these waterways, carrying about 12 tons of cargo each, complimenting but not replacing land-based transportation routes. After a flour merchant named Jesse Hawley published a series of essays in 1807 describing in remarkable detail how a canal could be constructed between the Great Lakes and Hudson River, predicting with extraordinary prescience the cost and benefits of such an endeavor, talk of such an undertaking in New York increased exponentially.

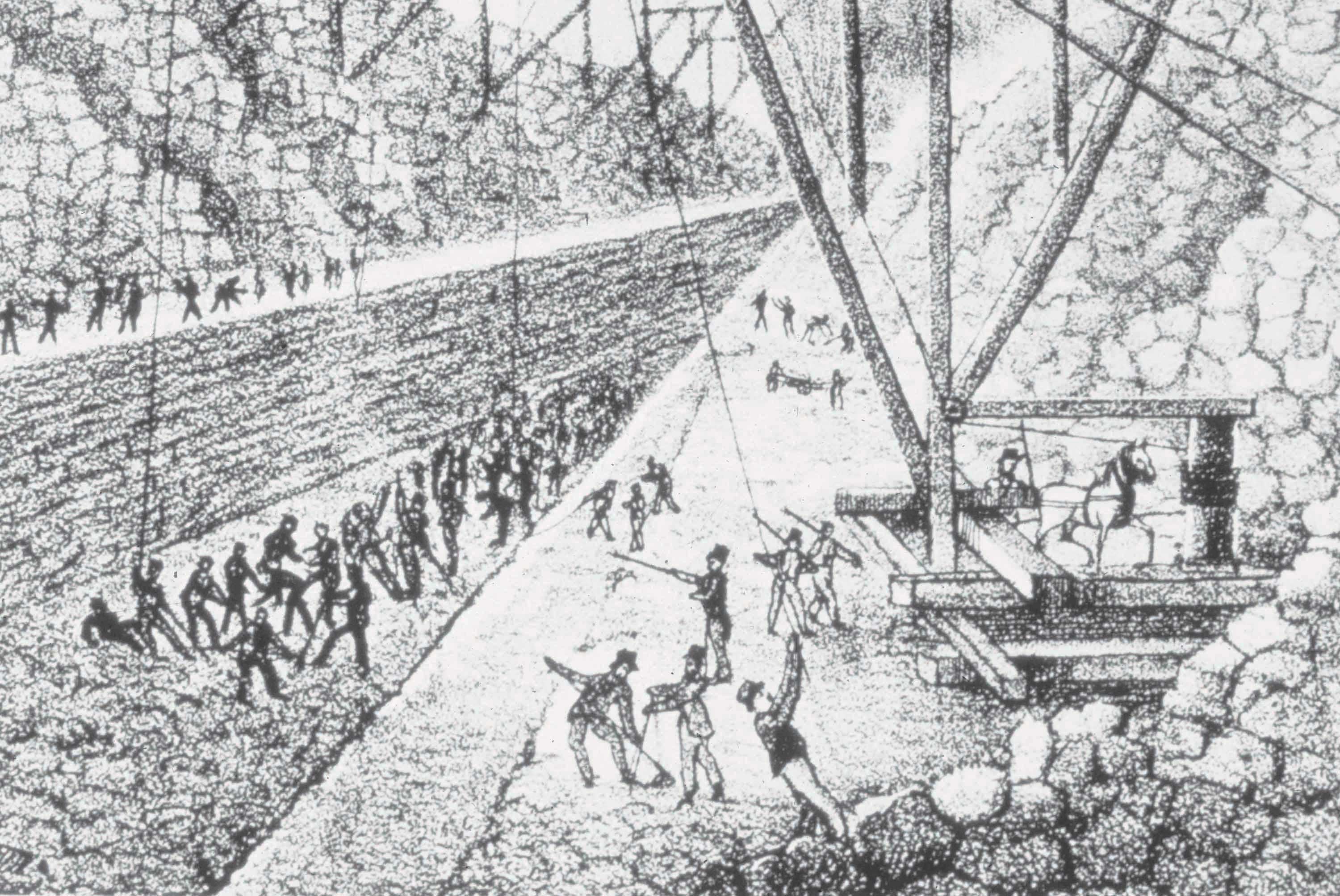

Part of James Geddes survey for a canal route near Rochester (NYS Museum) Many assumed that such a Herculean undertaking would require the Federal government, and others advocated a wholesale takeover of the Western Inland Lock Navigation Company by either the State or Federal governments. Such a takeover would allow additional improvements to be completed, and surely benefit the shareholders. However, Eddy, as Treasurer, soon realized that his company was ill-equipped and ill-prepared for the task. Instead, he began to believe that construction of a man-made canal, like that espoused by fellow New Yorkers Hawley, Assemblyman Joshua Forman, and prominent citizen Gouvernour Morris, was the only way to realize the full potential of connecting the Great Lakes with the Atlantic Ocean, and as such to European markets. Eddy was a strong supporter of State Senator DeWitt Clinton, former U.S. Senator and Mayor of New York. Though Eddy and his colleague, Senator Jonas Platt, thought the time was right for the State to take action on the Canal issue, neither possessed the political clout to advance the issue on his own. After a late night - perhaps all night - discussion on the merits of the canal and how to move forward on March 12, 1810, Platt and Eddy approached Clinton to see if he would take on the cause. Clinton agreed. Interestingly, given his widely accepted status as "Father" of the Erie Canal, this marks DeWitt Clinton's first formal association with the Canal project.

Construction of the deep cut near Lockport (NYS Museum) That morning, March 13, 1810, Platt advanced the motion on the floor of the Senate with support from Clinton. Clinton's support ensured the success of the measure, which was then transmitted to the Assembly for its concurrence. On March 15, 1810 the Assembly passed the measure, appointing Federalists Gouverneur Morris, Stephen Van Rensselaer, William North and Thomas Eddy, and Democratic-Republicans DeWitt Clinton, Simeon DeWitt and Peter Buell Porter as New York's first Canal Commissioners. New York was in the Canal business. After the survey of the Commission later that summer, followed by years of planning and deliberation interrupted by the War of 1812, the State Legislature finally approved construction in 1815. Construction began on July 4th, 1817 in Rome, NY. On November 4th, 1825, after nearly a decade of back-breaking labor by thousands of Irish Immigrants, Clinton arrived in New York Harbor aboard the Seneca Chief. Having traveled the Grand Canal from Buffalo, he then emptied a cask of water into the Atlantic Ocean off Sandy Hook, NJ, symbolizing the new connection which would change the world and transform New York into the Empire State. The legacy of the Canal Commission and its survey of the Canal route 200 years ago endures today as a reminder of the great resolve and ingenuity of those early New Yorkers who that day in March, 1810 heeded the words of flour merchant Jesse Hawley who wrote: "... if the project be but a feasible one, no situation on the globe offers such extensive and numerous advantages to inland navigation by a canal, as this!" |

CURRENT ISSUE

RECENT ISSUES

SYNDICATE

[What is this?]

POWERED BY

HOSTED BY

Terms of Service | Privacy Policy

Website Design By C3I